Last Updated on April 13, 2020

Bringing the Bennets to Life

Costume and Characterization in 5 Adaptations of Pride and Prejudice

Utter the words ‘Pride and Prejudice’, and many people – modest admirers as well as aficionados—will be able to pull their favourite edition from the shelf, quote pages off by heart, and recall where they were when they read the ending for the first time.

To help keep this site running: Willow and Thatch may receive a commission when you click on any of the links on our site and make a purchase after doing so.

For perhaps even more, however, an image will be conjured up based on one of the many successful television and film adaptations that have graced our screens for the past seventy years.

For me, Elizabeth Bennet can only be Jennifer Ehle, and Mr Darcy, Colin Firth. But for those of a different generation, it might be Laurence Olivier and Greer Garson that most succinctly and beautifully evoke one of literature’s most adored romantic couples.

Millenials on the other hand, may have been introduced to Austen through the prism of Pride and Prejudice and Zombies, a film in which the costumes have to withstand copious amounts of blood and guts. Not something you would naturally associate with Jane Austen, and an effort to – in one reviewer’s words – be ‘epic and crazy’ unfortunately resulted in an interpretation that represents ‘the lowest form of mashup’.

The truth is that this timeless story doesn’t need inserted horror in order to captivate its audiences, and a large part of its appeal lies in its ability to transport us to a genteel, privileged and beautiful world. An enormous part of that comes from the role of the costumes, and the dresses of Regency England seem to hold infinite appeal to twenty-first century audiences.

This is perhaps partly because they seem innately wearable: there are no hoopskirts or bustles, and Elizabeth Bennet’s ability to traipse through the countryside in a long skirt and bonnet, or to sprint along a lonely stretch of road, makes it easier for us to imagine ourselves in 1813 England. At the same time, the floaty empire-line dresses are ethereal and seemingly delicate, and their wearers seem to move with grace and time: a world away from the rush and roughshod of twenty-first century life.

But exactly how the costumes are tackled is a major concern (and a big responsibility) for productions that take on the task of recreating this much-loved world. Historical accuracy is, of course, key – as is the more complicated aim (often set by producers) of making a production ‘relevant’ to modern eyes.

I’m going to explore the costuming choices, mostly for female characters, in five of the best-known and loved adaptations of Pride and Prejudice. I will examine their level of success – and the ways in which that can realistically be measured – when it comes to creating faithful, attractive and practical costumes for Austen’s characters. Designers are playing with fire given the deep and fierce love that audiences hold for this story, and as we move from the first production in 1940 to the most recent, from 2013, contemporary considerations and aesthetic will be abundantly clear.

To what extent do the interpolations and artistic license taken by designers affect our enjoyment and our sense of what a production ‘should’ portray? How far does accuracy matter, and by what yardstick are we measuring it? – Lydia Edwards, fashion historian and author of How to Read a Dress: A Guide to Changing Fashion from the 16th to the 20th Century.

![]()

Starring Laurence Olivier and Greer Garson

For costuming pedants, there is on first glance a lot wrong with this film. First and foremost, the glaring change of date. Rather than being set in around 1813 (the book’s publication), the producers have set it in the 1830s: the Bennet sisters float about in puffs of silk and organza, complete with tall hair, layers of petticoats, huge sleeves and waists placed very decidedly in the ‘natural’ position. However, this is far from an oversight. In many respects, it is an entirely deliberate choice that’s perfectly understandable and in keeping with the mood of the time. The costume designer, Gilbert Adrian (known simply as ‘Adrian’) was also a prominent fashion designer, and his work for both epitomized glamour, elegance and striking silhouettes.

This is especially poignant and prominent for clothing designed during wartime; a chance for escapism to an apparently simpler, certainly more ‘romantic’ –and all the associations that word entails – time period. The straight, simple empire line dress of 1813 must have felt too close to the limits of rationing, which were soon to be felt across the US as well as in Europe.

For later audiences, such a relatively modest use of fabric would have served as a stark reminder of the forced simplicity of textiles and clothing during the Second World War.

The gown (below) worn by Garson for Darcy’s ‘second proposal’ scene is reminiscent of the froth and frills of other wartime costume film creations, such as the fancy dress ball gown worn by Joan Fontaine in Rebecca (1940, Irene Lentz), and of course, the white meringue confection donned by Scarlett O’Hara (Vivien Leigh) at the barbeque scene in Gone With the Wind (1939, Walter Plunkett).

Gone with the Wind had been a phenomenal success and the costumes were no small part of that, with a similar aesthetic shown in Joan Fontaine’s costume ball dress for Rebecca the following year.

As a designer for the stage as well as for couture, Adrian himself was drawn to the theatrical, the over-the-top, the glamorous. Perhaps his most famous creation was the white, froofy, frothy and unforgettable dress (below) made for Joan Crawford in Letty Lynton (1932).

Even Adrian was surprised at the level of buzz the creation provoked, and it was this that allowed him to become ‘conscious of the terrific power of the movies.’ The Lynton dress was not a million miles from the puffed sleeves and engulfing nature of the 1830s Pride and Prejudice gowns.

The broad shoulders of both styles give the wearer sartorial power in the physical barrier they create; the broadening of the body provides presence and strength.

It’s no surprise that this style accompanied women into the 1940s, arming them against the rigours of life on the home front and in service. In the same way, Elizabeth Bennet in Adrian’s version is asserting herself through her larger-than-life clothes, and Garson’s often haughty demeanor only emphasizes this effect.

Overall, I find it hard to condemn this film for its change of setting and banishment of the empire line. Wartime called for luxury and escapism on screen, and this is certainly what Adrian provided to a ration-weary public.

Pride and Prejudice (1940) is available to STREAM.

Pride and Prejudice (BBC) 1980

Starring David Rintoul and Elizabeth Garvie

Exactly 40 years after Olivier and Garson’s depiction of Darcy and Elizabeth, the BBC presented its first mini-series of Pride and Prejudice, with costumes designed by Joan Ellacot. This enjoyable adaptation, relatively faithful to the original text, is set roughly around the date of the novel’s publication, c.1813-15.

Several aspects of the female costumes appear slightly later in date; elaborate trimmings or ‘hem sculpture’ on skirts, profusion of lace on evening gown necklines and sleeves, and ornate trimmings on outer garments.

All these details suggest costuming closer to the 1816-20 mark, and this was most likely a case of the designer cherry-picking favourite elements from a range of fashion plates and original garments to produce the desired aesthetic.

Such fussy details also lend themselves well to contemporary late 1970s and – especially – 80s trends, and indeed, the benefit of hindsight shows us how close some of the costume details are to the contemporary shape.

A dress worn by Tessa Peake-Jones as Mary Bennet (above, left), with its collar frill, pouched sleeves and geometric print bears significant similarities to popular maxi dress characteristics, such as this mid-late 1970s Style pattern (right).

A dress worn by Tessa Peake-Jones as Mary Bennet (above, left), with its collar frill, pouched sleeves and geometric print bears significant similarities to popular maxi dress characteristics, such as this mid-late 1970s Style pattern (right).

This well illustrates the cyclical nature of fashion. Empire line maxi dresses, ‘granny’ styles and ‘Victoriana’ certainly took elements of their inspiration from Regency fashion, and were popularized by designers like Laura Ashley in the 1970s.

Looking ahead to the following decade, the wide lace collar on Charlotte Lucas’ (Irene Richard, below left) evening gown could have come straight out of a 1980s sewing pattern.

This is not to suggest that this adaptation of Pride and Prejudice’s costumes were merely copies of contemporary looks – far from it – but merely that they were inevitably influenced by leading fashion trends which were, themselves, purposefully ‘nostalgic’ and whimsical.

The wedding of Prince Charles and Lady Diana Spencer in 1981 epitomized this dreamy, romantic, nostalgic feeling which seemed to be synonymous with the word ‘historical’.

In fact, David Emanuel, Diana’s wedding dress designer, declared (A Dress for Diana) that the aim was to keep the bridal party’s dresses ‘romantic, historical and very pretty.’

Pride and Prejudice (1980) is available on DVD.

Pride and Prejudice (BBC) 1995

Starring Colin Firth and Jennifer Ehle

11 million viewers per episode. 12,000 copies of the VHS release sold in just two days. So much has been written about how this adaptation by Simon Langton got it right, and how and why it became as phenomenally successful as it did. No surprise, then, that its costumes held a power and an influence unknown in any previous Austen re-work. It seems to be a truth universally acknowledged that, aside from a few too many low necklines during the day on women’s gowns, the designer Dinah Collin was as close to accuracy is it’s possible to get. In her own words, the production’s costumes had to appear ‘fresh and light…as natural for each character as possible…The key is to make the clothes like real clothes from a wardrobe rather than a set of costumes worn by actors.’

Rather than be influenced by contemporaneous 1990s styles, the costumes so caught the public’s imagination that they in turn influenced current trends. The spate of Austen adaptations that followed – Emma (1996) with Gwyneth Paltrow and another later that year starring Kate Beckinsale; Sense and Sensibility (at the close of 1995), Persuasion (1995) prompted the production of empire-line styles in both couture and high street shops in the mid-late 1990s.

Collin also succeeded in making male costumes sexy rather than ‘sissy’, keen to avoid, for example, the overly frilled neckerchiefs/cuffs and abundance of knee breeches that seemed to dominate men’s clothing in earlier Austen period pieces. She achieved this partly through deep ‘country’ colours and thick textured fabrics, such as Darcy’s long, grey linen coat.

This tied in well with the similar earthy emphasis for Elizabeth’s wardrobe, with lots of browns, greens and creamy contrasts. This focus on characterization through costume was perhaps one of the greatest successes in the design of this version, and possibly the element that best allowed Collin to provide contemporary relevance.

‘After all’, she said, ‘everything we’re doing is an interpretation in the end – we aren’t making a museum piece’. She wanted to make the clothes attractive to a modern audience, an aim that was obviously successful given the resurgence of the empire line.

It is also, in some ways, probably easier to achieve this with Regency dress than with, say, eighteenth century panniers or 1860s crinolines. It’s much easier for us to imagine ourselves wearing them on a daily basis, despite the corsets and petticoats that were still required to provide the columnar shape of the gowns.

It is distant enough to retain that pretty, nostalgic whimsy that seems to be required, yet close enough in its apparent wearability (as mentioned previously, Elizabeth’s country walks – and sometimes, runs—are evidence enough of this).

At the tender age of 12 my Regency crush began in earnest after first seeing this adaptation. As I fell asleep at night I pictured myself in a long gown and spencer, walking through the streets of Meryton. I longed for a dress but didn’t know how to sew in those days, and being 13, didn’t have much in the way of money.

So (naturally) I wrote to a fashion agony aunt column in a national newspaper.

She responded in clear surprise that someone my age was asking, but advised me to check in the popular UK high street store, Miss Selfridge.

This wasn’t exactly accurate fare but I investigated. The dress was a yellow, floral, empire line, short-sleeved, calf-length summer frock with a round gathered neckline. Good in some ways but not the real McCoy, so I didn’t take that line of enquiry any further. However, the dress in question did illustrate a very real trend emerging in the mid 90s, one which also met with a 70s resurgence and with the arrival of ‘boho chic’. The fact that it had been suggested as an easily accessible Regency approximate by a fashion writer shows the level of influence the empire line was reaching, thanks in large part to Pride and Prejudice and the so-called ‘Austenmania’ that the production propelled.

Pride and Prejudice (1995) is available to STREAM.

Starring Matthew Macfadyen and Keira Knightley

Joe Wright’s adaptation premiered a decade after Simon Langton’s. As a film rather than a six-part television mini-series, it had far less time to tell a complex story. However, a significant amount of criticism has been leveled at the production that doesn’t stem from the way the plot was tackled, but rather; how the characters were portrayed. Setting the story in the time Austen wrote it is an understandable point of difference, but the resulting costumes don’t embody many of the social norms that a family such as the Bennets would have been accustomed to.

Nevertheless, as with any adaptation this is an interpretation, and one that aimed to encapsulate a fresh and different take on an old classic. Perhaps the fact that Wright didn’t, as magazine IndieWire commented in November 2005, ‘come across as very Jane Austen’, was beneficial because it would bring an aesthetic that was not ‘Masterpiece Theatre’. Wright wanted to avoid the ‘picturesque tradition’ because, to him, ‘messy is beautiful. I think tidiness is ugly and that’s just my aesthetic’. Perhaps the power of a director’s ego won out in this instance, and the film certainly has its fans who concur with Wright’s vision. Considering Jacqueline Durran’s costumes, I’m going to focus on a couple of specific examples, firstly Elizabeth’s Netherfield ball gown.

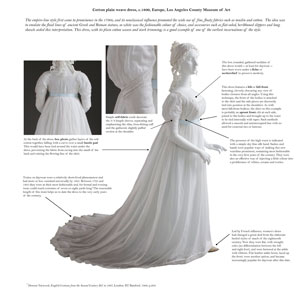

In line with the Regency fondness for white or light-coloured gowns emulating ancient Greek and Roman statues, many of the young female characters wear white in the evening. Elizabeth is no exception, though there are aspects of her best-known ball gown that single it out for consideration. The ‘wraparound’ effect of her bodice seems, on first viewing, like a very modern choice. However we can see from fashion plates and extant garments that this was an innovation used in the 1790s. (Fashion plate at right,1796)

In line with the Regency fondness for white or light-coloured gowns emulating ancient Greek and Roman statues, many of the young female characters wear white in the evening. Elizabeth is no exception, though there are aspects of her best-known ball gown that single it out for consideration. The ‘wraparound’ effect of her bodice seems, on first viewing, like a very modern choice. However we can see from fashion plates and extant garments that this was an innovation used in the 1790s. (Fashion plate at right,1796)

What is not so accurate is the very low waist, which creates an entirely different kind of aesthetic, and is more akin – in overall shape and fit— to this 2012 Monique Lhuillier bridal gown.

This also has something to do with the very modern and casual ways in which the female characters move (something also noticed in the 2009 BBC production of Emma). Young women at this time were schooled in deportment and posture, and the aim was to stand tall, elegantly; learning how to walk with grace in a long skirt and a corset that pushed the chest up high. Elizabeth may run through fields, but she takes care to do so when nobody else is around. At a ball, the common rules of etiquette would certainly apply.

The fit of Elizabeth’s dress was probably also informed by the actress who played her. Keira Knightley’s slim frame has been criticized as an unflattering one for period costumes, so by making her clothes more modern in appearance, the film scores points on the visual scale. Additionally, Joe Wright felt that the high waist was unattractive to modern eyes, so there was an extra personal reason for the shift. In many other respects the design of this version seems to be trying very hard to appeal to contemporary sensibilities, and could perhaps give its audience a little more credit.

A startling omission is the lack of any kind of jewellery or ornamentation in many of the ball scenes. Not only are their dresses usually indistinguishable from day styles, but the Bennet sisters frequently have no necklaces, fans, or even gloves. Such accessories were staples of propriety, and although not in the Bingleys or Darcys’ league, in comparison to most the Bennets were significantly well off. But to highlight their comparative poverty, Wright sees it necessary to imply that they were farming folk with livestock in the house, unable to dress in any way fashionably or even with much awareness of fashion.

Bingley’s intolerably snobbish sister, Caroline, is also given an interesting choice of ball gown. In many respects, it is utterly inappropriate for evening wear of this period. Completely sleeveless, it replicates a petticoat and would have been considered scandalous in the extreme in the 1790s.

On the other hand, it does mimic sleeveless early French Revolutionary styles, worn by a tiny percentage of society: the Merveilleuses with cropped hair and red ribbons worn around their throats to symbolize the guillotine. Such styles are mainly seen in portraits or caricatures of the period, and symbolize attitudes and a philosophy that are worlds away from anything the Bingleys would have embraced.

However, the dress does serve to single her out, and set her far apart from the other ball guests – a tactic that is successful in this instance. To a modern audience, her bare shoulders and noticeable cleavage might illustrate her wish to be at the centre of attention; possibly also her underlying aim to become Mrs Darcy. This is contrasted with Elizabeth’s demure clothing; the simplicity that only makes her physical charms and engaging wit stand out all the more. In this way, Elizabeth is presented to us as the far more attractive of the two.

The costumes of this adaptation are overall a good example of a self-consciously new vision; a risky attempt to break away from an enduring love for the 1995 series.

For some, its vision was too haphazard, too contemporary and too romcom. Others claimed that this was exactly what they most liked about it. Whichever camp you fall into, there is plenty in the costuming to argue for or against.

Pride & Prejudice (2005) is available to STREAM.

Death Comes to Pemberley (BBC) 2013

Starring Matthew Rhys and Anna Maxwell Martin

This made-for-TV dramatization is an adaptation of the crime novel Death Comes to Pemberley by P.D James.

Although not a Pride and Prejudice adaptation in the strictest sense it follows a number of familiar characters, including Darcy and Elizabeth who are now six years married and living contentedly at Pemberley. The couple are preparing for their annual ball when news of a murder halts all their plans.

One of the most interesting aspects of the costuming by Marianne Agertoft is that the film features flashbacks to when Elizabeth and Darcy met – to the ‘real’ Pride and Prejudice. These are set in the 1790s, and more faithfully than the 1790s of Joe Wright’s adaptation, with big hair and very high waists and billowy skirts.

The contemporaneous costumes continue the aesthetic of the 1995 version: simple, pretty prints for the women and linens in deep country colours for the men. Despite now being mistress of Pemberley, Elizabeth’s gowns are still relatively simple, though we can assume that the quality of the fabric far exceeds what her previous budget as Miss Bennet would have allowed.

The green dress seen below, which is her most frequently worn, illustrates some features common to the very early 1800s. From the top down, these include the round, gathered neckline sash in a contrasting colour, and long sleeves ending snugly just above the knuckle.

The gown also features a bib apron front, which was common from 1800 to around 1810. This was a detachable or free-hanging front panel that was attached to the front shoulder straps of a bodice. Fastening at the front in this way meant that the back of the bodice was left smooth and undivided. The same technique is seen on the light, youthful, printed dresses worn by Eleanor Tomlinson as Georgiana Darcy (right).

Death Comes to Pemberley is available to STREAM.

We must remember that these are costumes, made for fictional characters across a timespan of more than fifty years. Different filmmakers in different eras will naturally have differing views on what is beautiful, what their audience will believe to be beautiful, what their audience should deem to be beautiful, and how they might best influence future trends. Historical accuracy is sometimes given as an aim; sometimes it is blatantly at the back of the production teams’ mind.

As I pointed out in a recent article for The Conversation, we will inevitably look back on period films and television and say “that looks so 2017” without, yet, the benefit of hindsight. The very concept of accuracy may be something forever out of reach, but somehow it seems to matter even more when we are considering the adaptation of a story so universally loved as Pride and Prejudice. Its characters are as familiar to many of us as our own family and friends; we have grown up with them and revisit them many times throughout the course of our lives.

To take on the task of recreating these pivotal figures, in a way that will resonate with the majority of viewers, is a colossally brave undertaking. Yet the fact remains that no matter how people have come to know the classic, TV and film adaptations shape how generations have thought of the book and, furthermore, shape how new readers picture their heroes whilst reading. Gauging the level of success is a very personal thing, a very emotive thing; and it’s highly likely that fans will never be able to agree. The debate continues.

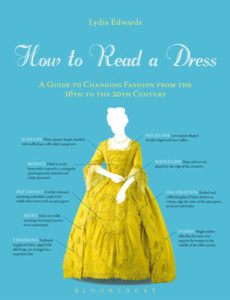

Lydia Edwards is a fashion historian and author of How to Read a Dress: A Guide to Changing Fashion from the 16th to the 20th Century. Fashion is ever-changing, and while some styles mark a dramatic departure from the past, many exhibit subtle differences from year to year that are not always easily identifiable. With overviews of each key period and detailed illustrations for each new style, How to Read a Dress is an authoritative visual guide to women’s fashion across five centuries.

Lydia Edwards is a fashion historian and author of How to Read a Dress: A Guide to Changing Fashion from the 16th to the 20th Century. Fashion is ever-changing, and while some styles mark a dramatic departure from the past, many exhibit subtle differences from year to year that are not always easily identifiable. With overviews of each key period and detailed illustrations for each new style, How to Read a Dress is an authoritative visual guide to women’s fashion across five centuries.

Each entry includes annotated color images of historical garments, outlining important features and highlighting how styles have developed over time, whether in shape, fabric choice, trimming, or undergarments. Readers will learn how garments were constructed and where their inspiration stemmed from at key points in history – as well as how dresses have varied in type, cut, detailing and popularity according to the occasion and the class, age and social status of the wearer.

This lavishly illustrated book is the ideal tool for anyone who has ever wanted to know their cartridge pleats from their Récamier ruffles. Equipping the reader with all the information they need to ‘read’ a dress, this is the ultimate guide for students, researchers, and anyone interested in historical fashion.

This lavishly illustrated book is the ideal tool for anyone who has ever wanted to know their cartridge pleats from their Récamier ruffles. Equipping the reader with all the information they need to ‘read’ a dress, this is the ultimate guide for students, researchers, and anyone interested in historical fashion.

This original, accessible take on fashion history is packed with color images, and each example garment annotated with terminology, key elements of the shape and construction, and other details of note. -C. E. Berg, Museum of History and Industry

If you enjoyed this post, you’ll want to wander over to The Period Films List. You’ll especially like the Best Period Dramas: Georgian and Regency Era Lists. Also be sure to see these Jane Austen inspired gifts, the article about Block Printed Cottons in the Georgian Era and The Jane Austen Travel Guide for suggestions of filming locations to visit when you are in England.

Catherine A. McClarey

February 12, 2024 at 3:36 pm (2 months ago)I’m watching the 1940 version of Pride & Prejudice on Amazon Prime Video this afternoon. I’ve read online (either in the pop-up trivia notes or the Wikipedia article) that the studio didn’t have enough Regency-period costumes on hand for the cast, and couldn’t import more from England because of World War II — which may well have encouraged the filmmakers to go with an 1830s look instead.

Danielle

January 17, 2021 at 10:49 pm (3 years ago)Most Millennials probably have been exposed to the 1995 version of Pride and Prejudice, considering the oldest of us are in our 40s and the younger end most definitely were exposed to the Keira Knightly 2005 version. I don’t know if you’re misinformed about what age range millennials are or you….don’t care, but your quip about millennials being exposed to Pride and Prejudice and Zombies first is just an ignorant and lazy opinion. I don’t even usually comment on people’s blogs but your comment made me so mad I had to say something.

Willow and Thatch

January 20, 2021 at 3:45 pm (3 years ago)Thanks Danielle, I’ll let our writer know and we can update the article.

Molly

July 12, 2020 at 10:55 pm (4 years ago)I promise that, as a millennial, our “version” is NOT pride and prejudice and zombies. You’re thinking of a younger generation. It is much more accurate to say that our version is the 2005 edition with Keira Knightley. Thanks.

Willow and Thatch

July 13, 2020 at 7:35 am (4 years ago)Thanks Molly – I guess that would be Gen Z / Zoomers?

Elmtree

June 24, 2020 at 10:35 pm (4 years ago)HBO Max has the 1940s version so I thought I would check it out and immediately could not watch it because of the costumes. Reminded me way too much of gone with the wind so I was not interested. I did not know they changed it to be in the 1830s.

I do love the aesthetics of the 2005 version even though some of the costumes weren’t correct (like you said, the sleeveless ball gown), but I completely understand the director wanting to have their own aesthetic of the book. Kind like how Greta changed up little women look.

1995 and 2005 are both my favorite because they both do so well at adapting the book and I think they both bring something to the table that other didn’t.

Elizabeth Lilly

January 31, 2020 at 4:16 am (4 years ago)I was very intrigued by your discussion of why different costuming choices were more suited to films and television shows made at different times. I would have just said that certain productions had historically incorrect costumes. You have far greater sympathy to the goals of the film directors and costume designers. It is very interesting! I now wonder if you could talk about the costume and especially the hairstyle choices made for Dr. Zhivago, which I hate, and find very distracting from the story. Yet I know that the costumes were adored when it came out, and led to a number of fashion trends, especially long coats with fur trim and embroidery. Clearly the styles struck a spark with the viewers of the time, no matter my opinion.

Clare

February 4, 2019 at 3:48 pm (5 years ago)My enthusiasm for the costumes in P&P is based entirely on the gorgeous look of Darcy’s britches after he has changed into decent attire to welcome Elizabeth to Pemberley, much more erotic than his coming out soaking wet from his swim. All my attention is focused on his stance and the very suggestive look of his thighs. Whether the britches are made of heavy silk or not, they could have been made of fine soft leather for their seductive appeal

(I’m an 84 year old woman and don’t often get a thrill from a movie!)

Greta

August 2, 2018 at 8:46 am (6 years ago)I really appreciate this article, as well as Edwards’ book– so much good information!

Hmph

January 28, 2018 at 5:38 pm (6 years ago)This millennial only knows Colin Firth as Mr Darcy.

Patty Halajian

August 2, 2017 at 10:50 am (7 years ago)I am a costume designer, and I found this article fascinating. I loved how the Greer Garson version was explained. It always bothered me that the costumes were so blatantly incorrect, but I see her point.

One thing I would point out, in the Kiera Knightly version was Mrs Bennett’s clothing. To my eye, she is clearly wearing a dress that would be dated at least 20 years earlier. I think that speaks to the fact that the family is poor, or at least, as mentioned, a farming family.

Becky Smith

August 1, 2017 at 2:25 pm (7 years ago)Loved reading this!

Rita Deodato

August 1, 2017 at 10:20 am (7 years ago)I absolutely loved this post! Thank you so much for all the hard work that was put into writing it. I don’t believe the 1940’s adaptation wardrobe is accurate, but I can understand why it was used and I do like to see it in that setting, but I really dislike the choices made for the 2005 adaptation. They are too modern and even simple when it comes to Elizabeth.

My favourite adaptation and wordrobe is from the 1995 adaptation, that’s the one I always imagine when I think of P&P 🙂

Ellie Dashwood

July 21, 2017 at 11:20 pm (7 years ago)I loved this article! I had heard that one of the reasons the Greer Garson movie used the later (and much puffier) style was because he was trying to create an idealized portrait of English country life that would resonate with the American public. The hope was this would make Americans want to enter WWII in order to protect their English heritage.

I do love the costumes in the 2005 version of P&P, but I also adore the costumes in Death Comes To Pemberley.

Jill

July 20, 2017 at 11:21 am (7 years ago)I had heard that the reason for costuming the Greer Garson/Laurence Olivier P&P film in 1830s styles was far more prosaic. The designer chose the 1830s because he had just finished costuming another early 1800’s-era film called “New Moon.”

Caroline

July 22, 2017 at 6:46 pm (7 years ago)I heard something along the same lines many moons ago in graduate school … that Adrian had just done a movie set in the early 1800s, and wanted to do something different. Since he had power in the studio system, he could dictate what he wanted to design. Though I should look this up to be sure it isn’t something apocryphal and not a myth that gets repeated and repeated.

Poppy

February 3, 2021 at 2:17 pm (3 years ago)i appreciate what you wrote about the 1940 version’s costumes. So many people hate it because of the costumes, but i think if you ignore them it is a very charming adaptation 🙂

MKH

July 20, 2017 at 2:23 am (7 years ago)I don’t understand/see this last feature:

The gown also features a bib apron front, which was common from 1800 to around 1810. This was a detachable or free-hanging front panel that was attached to the front shoulder straps of a bodice. Fastening at the front in this way meant that the back of the bodice was left smooth and undivided. The same technique is seen on the light, youthful, printed dresses worn by Eleanor Tomlinson as Georgiana Darcy (right).

Could you explain that more clearly?

Ellen Boruff

July 20, 2017 at 12:57 am (7 years ago)Enjoyed the similarities of 1940 and 1980’s costumes of the Bennett sisters. Costumes for opera productions also try to be historically accurate , but with the designers take of Slight adaptations.