Last Updated on June 7, 2023

In the second in a series of articles for Willow and Thatch about the cultural history of Masterpiece, Nancy West looks at how Masterpiece Theatre branded itself as the home for intelligent television.

To help keep this site running: Willow and Thatch may receive a commission when you click on any of the links on our site and make a purchase after doing so.

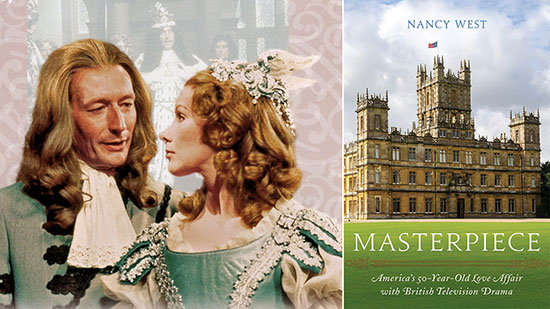

West is author of Masterpiece: America’s 50-Year-Old Love Affair with British Television Drama (Rowman & Littlefield, November 2020), a fascinating book that focuses not just on the long-running show, and its series that have been especially popular, but also why Masterpiece has been significant to Americans in particular.

“I fight to keep the brand name in people’s minds every day,” says Rebecca Eaton, former Executive Producer of Masterpiece (formerly Masterpiece Theatre). In an age when individual shows are disconnected from the studios that produce them, this fight isn’t easy.

Millions of Americans, even those who didn’t watch the series, recognize the name “Downton Abbey.” But not many Americans, beyond serious period drama fans, know that it was Masterpiece who first brought “Downton Abbey” to America in 2011.

During the 1970s and 1980s, however, Masterpiece was a powerful brand. The name signified quality, education, discernment, excellence. Way before the arrival of HBO, Masterpiece promised to deliver “smart television.” It got their first. It planted the flag. What’s more, Masterpiece promoted itself as a gateway to a life filled with books, art, culture ideas.

Masterpiece Theatre logo 1971 – 2007 TM and © PBS, Inc., all rights reserved

Growing up, I totally believed in that promise. So did my immigrant mother. During the 1970s, we lived in the crime-ravished city of Newark, N.J, and we turned to Masterpiece every Sunday night to escape. Most of the time, we had no idea what was happening. I was a kid; what did I know about Tolstoy or Benjamin Disraeli? And my mother, who secretly preferred “Columbo,” fared little better. Yet we’d watch Masterpiece religiously every Sunday night, huddled under the covers of our twin beds, hoping to flee Newark by way of England.

“For Viewers Like You”

Masterpiece’s most obvious claim to being smarty-pants television was its close affiliation with PBS, the station that immediately announced its intended cultivation of educated, discerning viewers with the slogan “Viewers Like You.”

PBS logo 1971 – 1984 TM and © PBS, Inc., all rights reserved

PBS logo 1971 – 1984 TM and © PBS, Inc., all rights reserved

In fact, PBS was founded only three months before Masterpiece –on October 5, 1970. Created out of intense political pressure to smarten up television, PBS nevertheless received little support from the government (and would encounter systematic hostility from the Nixon administration). Still, PBS offered something profoundly appealing: the promise of self-improvement, of aspiration.

As we all know, these are magic words for Americans. “Aspiration is about change,” says philosopher Agnes Collard. “It is not only about becoming a different person but also about appreciating the values distinctive of that kind of person.” Vital to PBS’s founding was its promotion of certain values—education, artistic appreciation, beauty, social awareness, civility—that audiences would not only come to cherish but also enact.

Within a few months, lavish descriptors not commonly ascribed to television in the 1960s—“quality,” “excellence,” sophisticated,” “thoughtful”—encircled PBS like a halo. But it needed a program to bolster and stabilize it: a sparkling, surefire series with big-time aura. WGBH’s president, Stan Calderwood, was convinced that Masterpiece would be that series. Others at WGBH and PBS had their doubts. They questioned the appeal of period pieces for Americans (imagine!), especially in a climate of social fracture, and they bristled at the notion of using British imports rather than native drama.

But audiences loved Masterpiece. Responses to the program’s inaugural series, The First Churchills, were downright gushy—and not because “The First Churchills” was masterpiece drama. The series had fine acting and sparkling dialogue, to be sure. But it was really a lot of huggermugger, cluttered with troops of actors you couldn’t identify and plot lines you couldn’t follow. No Matter. What viewers liked was the idea behind Masterpiece Theatre. They wanted to be transported to England. To hear its accents and breathe its history. They wanted to see actors like Derek Jacobi and Glenda Jackson perform right in front of them, as if they had front row seats at London’s Prince Edward Theatre.

Over the next several weeks, reviews and fan letters were giddy with gratitude to PBS for bringing Masterpiece Theatre to television—and inspiring viewers to pursue their own liberal education. The New York Times called “The First Churchills” a “revelation on the potential of television to combine intelligence with solid entertainment.” Another reviewer praised the program’s “gifts of subtlety and nuance” in a “world of pow and blam, which equates reality with a sledgehammer.”

Quickly pronounced a hit, Masterpiece Theatre gave PBS an identity, imbuing it with an air of quality, confidence, and tradition. It raised PBS’ primetime audience by a whopping 30 percent between 1971 and 1972. And it also exercised an undeniable influence on television in general.

By the mid-1970s, WNET was producing a blockbuster historical drama called The Adams Chronicles; NBC was adapting Dickens and Austen; and several miniseries that would become television masterworks—Rich Man, Poor Man, Holocaust, and Roots—were underway.

Meanwhile, a bevy of other British series, such as “Monty Python’s Flying Circus,” were airing on PBS, prompting PBS president, Larry Grossman, to remark, “I can’t imagine where American public television would be if the British didn’t speak English.”

But PBS and Masterpiece Theatre weren’t only committed to an aspiration of quality. They also wanted to recapture a lost era of television excellence.

“Television Playhouses”

Not long ago, before our present era of television splendor, people talked about another “Golden Age of Television.” Like all golden ages, this one evoked awe for a glorious past and dismay over a crummy present. The “age” in question was roughly 1948-1960, when American viewers could tune in any night of the week to watch live performances of plays via programs called “anthology dramas.”

These dramas were the forerunners to Masterpiece Theatre. Presenting a variety of drama with award-winning scriptwriters and method-trained actors, they suggested that a natural intimacy existed between the new, uncertain medium of television and the centuries-old, venerated medium of theater.

In America, the first anthology drama was NBC’s Kraft Television Theatre (1947-1958). Others quickly followed, including Studio One (1948-1958), The Philco Television Playhouse (1948-1955), and Lux Video Theatre (1950-1957). Airing between 7:00 p.m. and 9:00 p.m., they typically ran for an hour or hour and a half. With their air of high culture, they soon became the darlings of critics and cognoscenti who thought they possessed a quality other shows lacked. Reviewers extolled the talent of performers like Rod Steiger, Jack Lemmon, and Grace Kelly, who all cut their teeth on anthology drama. And they praised the scripts, many of which were classic adaptations like A Christmas Carol and Alice in Wonderland.

In the eyes of critics and many viewers, then, anthology dramas aspired to the standards of legitimate theater while everything else on TV dumbly imitated Hollywood or vaudeville. They also culled and curated the “very best” plays for Americans, collecting and cohering drama while exalting it. Nearly two decades later, this perception would profoundly shape the reception of Masterpiece Theatre.

“The Thinking Person’s All My Children”

In my previous installment on Masterpiece, I noted how the show was inspired by the overwhelming popularity of The Forsyte Saga, which aired in America during the fall months of 1969. A 24-part miniseries, “The Foryste Saga,” like many Masterpiece productions to come, was really soap opera.

And yet, critics praised it for its “intelligence” and “quality.” Why? Because “The Foryste Saga” had a top-shelf cast and an exquisitely written script, penned by an award-winning team of screenwriters that included Donald Wilson, the co-creator of “Dr. Who.” It was based on a trilogy of novels that had won its author the Nobel Prize for Literature. And it was British! And old! In American minds, “The Forsyte Saga” wasn’t guilty television at all. It was aspirational.

And so it goes with many of the dramas airing on Masterpiece, from Upstairs, Downstairs (1974-77) and I, Claudius (1979) to Downton Abbey (2011-2016) and Les Misérables (2019). These shows deliberately muddle high and low forms. They punctuate the heaviness of period drama with other genres, modes, and styles. Consequently, viewers can pursue the hard work of aspiration—reading good books, learning history, appreciating the craft of theater-trained acting—while enjoying such low-grade delights as sudden plot reversals and last-minute rescues.

“How Did the Wasteland Get So Beautiful?”

The question above comes from an article by TV critic Eric Adams, remarking on the variety and excellence of our current television landscape. Adams goes on to point out that television is a “medium without a past,” observing that in its relentless drive to keep its content fresh and flowing, television has built an antipathy to its own history.” This observation is especially true today, when critic after critic seems unwilling to go any further back, says Adams, than 1999, the year when “The Sopranos” debuted and Television Got Good.

But as this brief account shows, it was Masterpiece who first introduced viewers to a new world of television excellence. And as we’ll see next time, it also gave us one of the most popular and beloved series of all time, a series that arguably shaped period drama more than any other single influence: “Upstairs, Downstairs.”

For a list of the period dramas that have aired on Masterpiece, season by season, see this page.

Nancy West is author of Masterpiece: America’s 50-Year-Old Love Affair with British Television Drama (Rowman & Littlefield, 2020), in which she provides a fascinating history of the acclaimed program.

West combines excerpts from original interviews, thoughtful commentary, and lush photography to deliver a deep exploration of the television drama. Vibrant stories and anecdotes about Masterpiece’s most colorful shows are peppered throughout, such as why Benedict Cumberbatch hates “Downton Abbey” and how screenwriter Daisy Goodwin created a teenage portrait of Queen Victoria after fighting with her daughter about homework.

Featuring an array of color photos from Masterpiece’s best-loved dramas, this book offers a penetrating look into the program’s influence on television, publishing, fashion, and its millions of fans.

West is professor of English at the University of Missouri and the author of Kodak and the Lens of Nostalgia (2000) and Tabloid, Inc.: Crimes, News, Narratives (2010). Her books have led to appearances on PBS’s American Experience and the BBC’s Genius of Photography as well as keynote speeches at the National Gallery of Art in Washington, DC, the London School of De- sign, and the Amon Carter Museum. She is a regular contributor to Written by Magazine, the Atlantic, the Chronicle of Higher Education, and the Los Angeles Review of Books. She is currently writing a memoir, set in the 1970s, about movies and childhood trauma.

If you enjoyed this post, wander over to The Period Films List.