Last Updated on June 7, 2023

Viewers who tuned in to watch Masterpiece Theatre weekly on Sunday nights in its early years know the name Alistair Cooke. But who was he, and how did he come to be the beloved face and voice of the program?

To help keep this site running: Willow and Thatch may receive a commission when you click on any of the links on our site and make a purchase after doing so.

In the fifth in a series of articles for Willow and Thatch about the cultural history of PBS Masterpiece, Nancy West shines a light on the British-American broadcaster and journalist, and what he brought to the table.

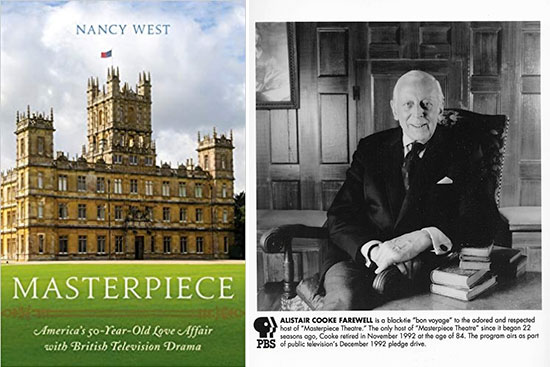

West is author of Masterpiece: America’s 50-Year-Old Love Affair with British Television Drama (Rowman & Littlefield, November 2020), a fascinating book that focuses not just on the long-running show, and its series that have been especially popular, but also why Masterpiece has been significant to Americans in particular.

From 1971 to 1992, one person embodied Masterpiece Theatre: Alistair Cooke, the show’s original, inimitable host. It was he, silver haired and debonair, sitting in that library, whom people thought of when they thought of the show.

Alistair Cooke (1908-2004) is slowly slipping into the vast limbo where the once famous but now nearly forgotten reside. In most cases, this is no great tragedy. In Cooke’s case, it is.

He made a brilliant career of navigating between America and Britain, illuminating each country to the citizens of the other. Cooke was a cicerone, a cultural interpreter, and a smoother of transatlantic tensions.

Born in the working-class town of Salford, England, he came to the States in 1932 to study theater at Yale. He intended on staying two years, but the following summer he rode across country and, amazed by the contrast between Britain’s postwar weariness and America’s “tremendous vitality,” abandoned theater for a journalistic career.

In 1946, Cooke began broadcasting a weekly radio show for British audiences called Letters from America. A strong flavor of anti-American sentiment pervaded England at the time, stirred by Roosevelt’s open condemnation of Britain’s rule over India and the perceived arrogance of American soldiers stationed in England. Cooke thought a radio program could help bridge the fissure between the countries.

Pitching his show to the BBC, he imagined it as “a weekly personal letter,” written for his native countrymen, about American life and people and places.” Letters from America aired for forty-six years, breaking every broadcast record because of how Cooke unfailingly charmed his listeners with peerless observations of American life.

Stan Calderwood and Christopher Sarson, the producers most responsible for Masterpiece Theatre’s conception and early design, wanted Cooke from the start. Savvy and intuitive, like all good producers, they knew the show needed an authority on British history and culture, someone smart and affable who could set each episode in an informative but entertaining context.

Cooke was “the only choice,” Sarson said. But when he called to offer Cooke the job, Sarson was turned down flat. Hearing a few weeks later that his quarry was visiting Boston, Sarson invited him to a favorite local restaurant and lured him with his favorite scotch.

When Cooke politely declined again, Sarson persuaded Cooke’s daughter, Susan, to work on her father. Cooke agreed to a thirteen- week contract one month before the show’s premiere, never imagining he’d stay longer—certainly not for twenty-two years.

All Alistair Cooke was hired to do was deliver weekly introductions and closing remarks spanning thirty seconds to four minutes. But those accompanying words, and the persona he created, would discernibly link Masterpiece with the ideal of high culture.

Cooke’s contribution to Masterpiece was to invert Letters from America, his across-the-pond agility now illuminating Britain for Americans. And in keeping with Masterpiece’s aspirational bent, he did so with extraordinary erudition. A man who could distill the story of the English Civil War into a paragraph or tell you what color geraniums (red) Dickens planted in his garden, Cooke was a living footnote, the Lord Google of his era. And his grammar was impeccable.

Yet for all his learnedness, there was no academic tweediness about him, nothing of the prig or snob. Vigorous and agile, possessed of a mischievous grin and puckish sense of humor, Cooke would have had undergraduates flocking to his courses.

“In the United States he was the very model of the English gentleman,” writes the Encyclopedia Britannica. Cooke might have chuckled at the description, but it’s true nonetheless—and it was paramount to his success on Masterpiece. The British gentleman possesses, among the usual attributes of gentility and refinement, a relaxed relationship to knowledge. He is versatile and responsive to a variety of subjects, drawn to them by feeling rather than professional necessity. It was this eclectic bent, this approach to learning in an inductive and miscellaneous way, that gave Cooke his own gentlemanly charisma.

His passion for knowledge inspired fans of Masterpiece to be articulate, better read, well-traveled, and above all, curious about the world. It didn’t hurt that he wore suits by Hawes and Curtis, outfitters to the Duke of Edinburgh.

Cooke always wrote the introductions and closing remarks for Masterpiece himself, banging them out on an old manual typewriter as he sat at his desk, in his red-walled study overlooking Central Park. On the day of the taping, he would retreat to a small corner of the Masterpiece studio to memorize his to memorize his script (“No Teleprompters; No Makeup” were his inviolate broadcasting rules).

And because he had the memory of a dolphin, it took him no more than a half hour to commit five pages to heart. Once the filming began, he would recite his script as if he had just thought of it all, flubbing on purpose or improvising every once in a while to make the whole thing seem natural. “It’s an old-fashioned prescription, tougher on the memory and the nerves,” he wrote. But the effect was to make his audience feel as if he were speaking directly to them.

Cooke wrote over five hundred scripts for Masterpiece loaded with sharp, witty, and often profound observations about British history and culture. If culled, they’d make a sprightly collection. From them, we learn the details of Dostoyevsky’s gambling addiction, Thomas Hardy’s bouts of depression, George Eliot’s peculiar education at her father’s side, and Dickens’s disastrous reunion in midlife with his first love. We also get memorable encapsulations of figures such as these:

Of Noel Coward: “Glib in a grim time, he was the twenties dude in a poor post-war society.”

Of Dickens: “He was egocentricity incorporated.”

Of “Vanity Fair’s” Becky Sharp: She is “poor but pretentious, genteel but on the make, one of the most accomplished bitches in fact or fiction between the fall of Rome and the rise of Las Vegas.”

Alistair Cooke retired in 1992, the same year Johnny Carson, another ace conversationalist and TV institution, stepped down as host of the Tonight Show. Masterpiece considered over 150 candidates to replace him, finally landing on Russell Baker, the esteemed New York Times columnist. But Baker never seemed comfortable in the role.

How could he?

No one could ever quite embody the aspirational bent of Masterpiece like Cooke, the working-class boy who got a full ride to Cambridge and, at twenty, changed his name from Alfred to the much more elegant Alistair. He embodied the British ideal of the gentleman and achieved the American ideal of a self-made man.

To play off his own words, he was Masterpiece, Inc.

For a list of the period dramas that have aired on Masterpiece, season by season, see this page.

As part of The Linda and Andrew Egendorf Masterpiece Theatre Alistair Cooke Collection, a complete list of the programs presented during Alistair Cooke’s tenure as host with descriptions, along with clips of Cooke’s introductions and conclusions for each episode, are being made available online as they are digitized.

Nancy West is author of Masterpiece: America’s 50-Year-Old Love Affair with British Television Drama (Rowman & Littlefield, 2020), in which she provides a fascinating history of the acclaimed program.

West combines excerpts from original interviews, thoughtful commentary, and lush photography to deliver a deep exploration of the television drama. Vibrant stories and anecdotes about Masterpiece’s most colorful shows are peppered throughout, such as why Benedict Cumberbatch hates “Downton Abbey” and how screenwriter Daisy Goodwin created a teenage portrait of Queen Victoria after fighting with her daughter about homework.

Featuring an array of color photos from Masterpiece’s best-loved dramas, this book offers a penetrating look into the program’s influence on television, publishing, fashion, and its millions of fans.

West is professor of English at the University of Missouri and the author of Kodak and the Lens of Nostalgia (2000) and Tabloid, Inc.: Crimes, News, Narratives (2010). Her books have led to appearances on PBS’s American Experience and the BBC’s Genius of Photography as well as keynote speeches at the National Gallery of Art in Washington, DC, the London School of De- sign, and the Amon Carter Museum. She is a regular contributor to Written by Magazine, the Atlantic, the Chronicle of Higher Education, and the Los Angeles Review of Books. She is currently writing a memoir, set in the 1970s, about movies and childhood trauma.

If you enjoyed this post, wander over to The Period Films List.

Susan E. Roche

January 10, 2021 at 10:02 pm (4 years ago)Ali stair Cooke achieved one of the highest honors that America could bestow:

A character on Sesame Street, ❤️